The idea behind the electric vehicle is not new. In fact, electric cars once shared the road with steam-powered carriages and early petrol engines at the turn of the twentieth century. They ran quietly, produced no smoke, and appealed to city drivers who valued simplicity over speed.

However, their prominence faded as petrol-powered vehicles, notably with Ford’s Model T revolutionizing mass production from the 1910s, offered longer ranges and quicker refueling, shifting the automotive landscape also across Europe and beyond.”

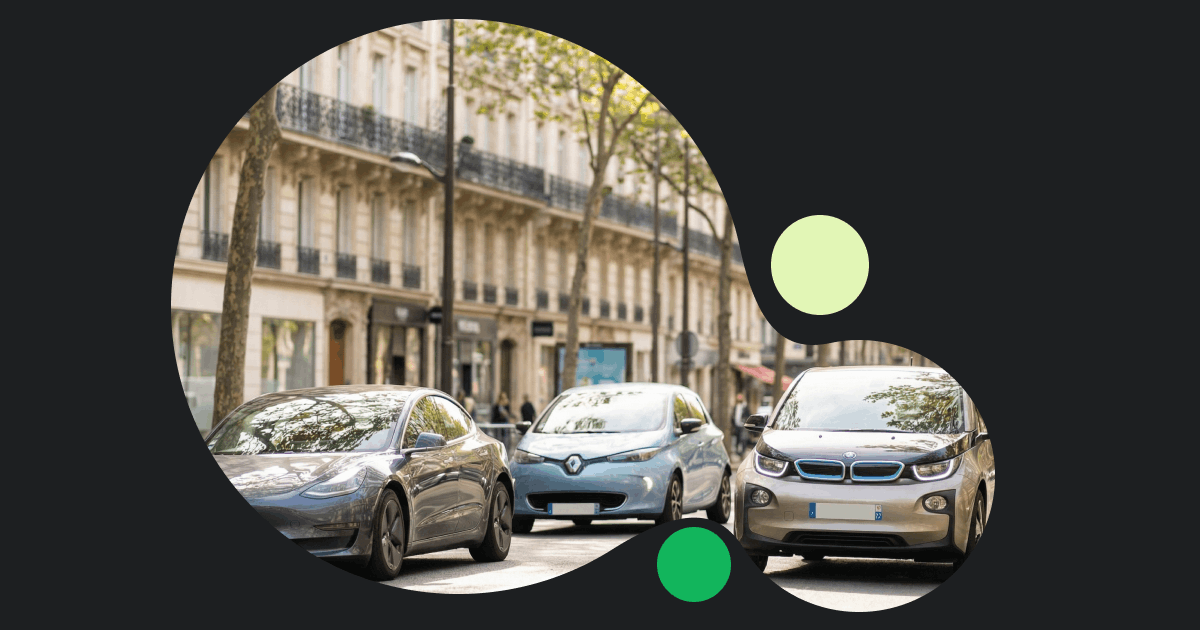

Now, the EVs have returned, not as a novelty but as a serious alternative to internal combustion engines (ICE). Batteries store more energy than ever, and EV charging stations no longer feel rare. Cities are seeking ways to reduce air pollution, while drivers grow weary of rising fuel costs and the heavy maintenance demands of combustion engines.

Ask ten people why they want to drive electric, and you’ll get ten different answers. Some care about emissions, others want to skip the petrol station, and more than a few fall for the quiet, smooth ride. Whatever the reason, one question usually comes first.

What Is an EV?

The term “EV” stands for electric vehicle, which uses electric motors for propulsion instead of a petrol or diesel engine. If you’re searching for the EV meaning, it’s simple: an EV is any vehicle that runs fully or partially on electric power, typically using a rechargeable battery to drive an electric motor. In Europe, fully electric cars now make up over 17% of all car sales, with plug-in hybrids adding another 8.5%.

But what is an EV in practice? When you press the accelerator in an EV, power moves from the battery to the motor almost instantly. There’s no combustion, no shifting gears, and no exhaust. The result is quiet, smooth, and remarkably responsive. You’re not waiting for the engine to catch up — the power is right there in any situation.

Electric vehicles don’t just feel different. They operate under a fundamentally simpler system. Fewer moving parts. Less heat. Fewer things to fix. That’s part of the appeal.

How Electric Vehicles Work

Even if the EV definition is easy enough to grasp—the idea of a car powered by electricity rather than petrol—the engineering behind it is more complex. An EV carries a high-capacity battery—usually lithium-ion—mounted under the floor or in the chassis.

That battery sends electricity to one or more motors, which turn the wheels. You don’t shift gears, as near EVs use a single-speed transmission (reduction gear) rather than a multi-gear system, as electric motors deliver instant torque across a wide range.

Aand thus there’s no transmission in the traditional sense, with a few rare exceptions like the Porsche Taycan, where you get a two-speed gearbox for performance. The result of no gear changes feels surprisingly natural. Everything responds without fuss, there’s no dramatic engine noises, and the heavy battery under the floor gives the vehicle a low center of gravity, making EVs great to drive.

Here is also where it gets clever. When you brake, the car doesn’t just waste that energy as heat as with usual ICE cars. Instead, slowing down in an EV sends some of the energy back to the battery, a process called regenerative braking. It’s efficient and changes how the car feels, especially when you drive in stop-and-go traffic. You’ll probably notice it early—lifting your foot slows the vehicle more than expected. After a few days, you start timing your lifts like muscle memory. The regenerative braking strength is adjustable in most EV models, and can go as far as creating a one-pedal driving experience, where the regenerative braking is so strong when lifting your foot from the pedal that you don’t have to use your brake pedal nearly as often.

There’s another benefit that most people don’t talk about enough with EVs: maintenance. Maintenance savings can reach €1,000-€2,000 per year compared to ICE vehicles, per European Commission data. There is less that needs attention as you can do without oil changes, timing belts, spark plugs, or complex cooling systems. Some EV owners joke that their biggest regular cost is windshield washer fluid. And that’s only partly a joke.

Types of Electric Vehicles

When someone says “electric car,” or “EV” they could mean a few different things. An EV, or electric vehicle, for most people is any vehicle that uses electricity for propulsion, but not all EVs are built the same. And some consider only purely battery-electric car an EV. So, what is an EV in terms of its types?

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs)

Battery electric vehicles are what you’d call the purest forms of electric vehicles. There is no fuel tank, tailpipe, or engine—just a battery, electric motor(s), and a plug to charge it. You recharge it, drive it, and can avoid gas stations completely. If you want a clean break from combustion, this is where it happens.

Nowadays, the battery range is large enough, averaging at around 400 kilometres, to make the fully electric versions quite competitive.

Currently, these pure electric vehicles make up 17.1% of all cars sold in Europe. In other words, every sixth car sold in Europe is already fully electric today.

Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs)

Plug-in hybrids are a category that tries to give you the best of both worlds. You get a decent all-electric range—usually enough for your daily errands of around 40 kilometres —but a small gas engine is also on board. If you run out of charge, the engine takes over. This offers peace of mind for some people, especially those without access to home charging.

However, a PHEV only makes sense if you really charge it often enough, and currently most analyses point at people not really plugging it in often enough, making them mostly rely on the gas engine and ending up polluting more over the lifetime of the vehicle. Since there are two powertrains to maintain, PHEVs are only the best of both worlds if they are used correctly.

Currently, these plug-in hybrids make up 8.5% of all cars sold in Europe. In other words, one in twelve cars sold in Europe is a plug-in hybrid today.

And as the traditional use of the word EV is adding battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) together, the EV market share in Europe is already at 25.2% today, with every 4th car sold falling into this category.

Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs)

Hybrids do not have a way to plug in and charge them, even though they have a small battery in the car. They use a gas engine with an electric motor assist and the battery charges while you drive. This improves the fuel economy without asking anything different from the driver compared to regular ICE vehicles. If you’ve ever driven a Prius, you’ve driven an HEV.

Now, these are indeed called hybrid electric vehicles, but in most cases, are not really considered as an electric vehicle, and rather as an ICE vehicle.

Now, hybrids have become the dominant car type in European car sales, with 35.3% of all car sales in Europe today being traditional hybrids.

Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs)

Fuel cell vehicles, also sometimes called hydrogen cars, are also a form of EVs, but are currently still rare on our roads in Europe. Instead of storing electricity in a large battery, FCEVs create their own electricity onboard using hydrogen and a fuel cell. The only byproduct is water vapour, making them exceptionally clean in terms of emissions.

However, hydrogen refueling infrastructure has not yet been built out enough for widespread adoption, with most of the pilot projects for both infrastructure and hydrogen car purchases concentrated in Germany and France, and just 1202 hydrogen cars were sold in all of Europe in 2024.

Charging and Everyday Life

To continue with infrastructure, what is EV charging? At first glance, charging an electric vehicle (EV)—a car powered entirely or partially by electricity instead of petrol—might seem like the biggest change for new drivers—and in some ways, it is.

But probably not in the way you’d expect. EV charging is a total win if you have a garage or a driveway where you can plug in, and that would make EV charging even faster than when you own a fossil-fueled car, as it takes just a few seconds to plug in! At a basic level, there are three categories of EV charging in Europe (using Type 2 or CCS connectors):

- AC slow charging, often also called home charging, uses a standard household outlet (230V). It delivers ~3-7 kW, adding 10-20 km of range to your EV per hour. This is practical if the car sits at home a lot, and for example adds 100-200km of range at home in 10 hours overnight

- AC fast charging can mostly be found at workplaces or some public sites, and uses a dedicated wallbox to deliver up to 22kW. This can add up to 50-100km of range in an hour, and a few hours of charging is usually all you need.

- DC Fast Charging is what you’ll find nearly exclusive in public charging sites dedicated for EV charging or added to common locations like shops. These use dedicated fast charging hardware that deliver from 50kW all the way to now-common 350kW, and are great for use when you’re in a hurry or roadtripping. These chargers can get your battery back to around 80% in less than half an hour.

Companies like Eleport are helping expand the network of EV charging stations across cities and major roads across the Baltics, Poland and Central Europe.. Planning a road trip in an EV still requires some prep, but the gaps are closing fast. Use Eleport’s charger map for real-time availability of the DC fast chargers.”

Why Drivers Make the Switch to EVs

Whatever the entry point, the same advantages in switching to EV tend to come up:

- Lower running costs. Electricity is usually cheaper than petrol with €0.04-0.06 cost per km vs. €0.10-0.15 for petrol (per European Commission data), and fewer moving parts also mean fewer surprise repairs.

- Quiet and comfort. No engine noise makes for a calm cabin, especially in traffic.

- Performance. That instant torque isn’t just fun.t’s also useful for confidently overtaking, merging, or pulling away from a stoplight.

- Smart systems. The energy to power an EV can be produced at home, integrates well with smart energy systems. And charging at home is super easy.

- Fewer maintenance headaches. No oil, fewer fluids, and less wear on the brakes. You’ll spend less time at the shop and more time driving.

- Your car gets better over time. EVs already often offer a highly digital experience, and they are upgraded constantly over the air.

- They care about the surrounding nature. Not only do the EVs avoid the tailpipe pollution in the air of our cities, EVs have also 73-78% lower lifetime CO2 than ICE vehicles when including production (ICCT 2025 report). The EVs start winning over ICE in emissions per every kilometre after 17000th km on average, since the battery production is heavier initially. That’s just 1-2 years of driving to start offsetting ICE emissions.

The design language of EVs often reflects their mindset—clean dashboards, software-based controls, and regular updates. They feel like the future, but in a good way. Of course, there are some manufacturers that have tried to make their EVs look as close to their ICE cars as possible, so they could ease the transition.

What to Keep in Mind

Of course, electric cars are not perfect. There are things to consider, especially if you drive long distances often or live in a region without a strong charging network and no home charging.

- Upfront price. EVs can cost more initially, although incentives often help.

- Range concerns. While many EVs now offer 300+ km on a charge, cold weather, high speeds, and hilly terrain can reduce that. However, large EV owner surveys show, that range anxiety is a significantly larger concern for people before buying an EV, and once they get and drive one, the anxiety drops significantly.

- Charging time. Even with fast charging, you’ll still need to pause longer than at a pump. It’s not usually a problem, but it can change some of the plans. Smart route-planning apps help a lot in that.

- Battery life also matters. Most EVs hold up well over time, and manufacturers offer warranties that cover 8–10 years. According to large sets of existing EV fleets, most modern EVs only lose 1.8% of their battery health per year on average (per Geotab). That means after 8 years, most batteries still retain over 85% of their capacity.” Still, it’s good to understand what’s covered and how much a future replacement might cost, just like you would with any high-value part.

Where It’s All Headed

Look around, and the direction is obvious. Major automakers now invest billions into EV development to comply with Euro 7 standards (2025) and the EU’s 2035 zero-emission target. Cities push for cleaner air and quieter streets. Younger drivers grow up expecting climate-conscious design, along with digitally advanced vehicles, as a baseline, not a bonus.

More EV models hit the market every quarter, with larger batteries, quicker charging, and lower prices. Some brands have committed to fully electric lineups within the next decade, as they are also challenged by the new fully electric brands, many of which are here to stay and gaining serious traction.

Charging networks like Eleport continue to expand along highways and within neighbourhoods, offices, and shopping centres. The shift to electric power is inevitable because it solves problems that gas engines can’t solve.

Final Thoughts

So what is EV, really? It’s more than a technical term. Driving something simpler, cleaner, and often more enjoyable is a choice.

It doesn’t mean giving up performance. It doesn’t require sacrificing convenience. In many ways, it’s the opposite. Driving electric redefines what we expect from a car. And once you experience it, it’s hard to return to ICE. In fact, that’s what nearly all EV owners say – they do not intend to ever turn back to a fossil-fuel vehicle.

If you are curious about the EV models available in Europe, check out the EV database that holds details on the latest EVs you can find on our roads. Once you get going in an EV, explore your reliable charging options in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, or Central Europe with Eleport’s EV charging network.